Photo © Adine Sagalyn

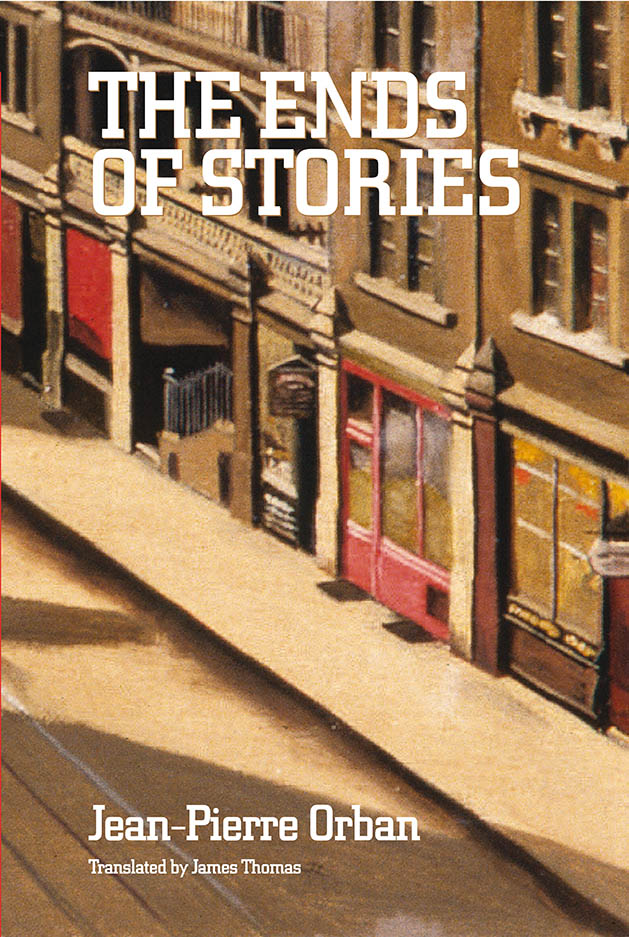

Photo © Adine SagalynTHE ENDS OF STORIES (translation of VERA in English) is published by Francis Boutle Publishers, London.

For other foreign rights, please contact Geneviève Lebrun-Taugourdeau, Le Mercure de France:

+33 (0) 155 426 195

Jean-Pierre Orban

J.-P. Orban was born in Belgium of a Belgian father and an Italian mother.

He spent his childhood in Africa. He now lives in Paris after having lived in Brussels and London.

He has written in French for the theatre, for children and young adults, and has published many short stories in literary magazines and collective works.

His novel Vera, published in 2014 by Le Mercure de France (Gallimard Group) and translated into English with the title The Ends of Stories won several prizes:

Prix du meilleur premier roman français 2014

Prix Saga du meilleur roman francophone belge 2015

Prix de l’Académie des lettres françaises de Belgique

Prix du Livre européen 2015 (the “Europe Book Prize 2015”) awarded at the European Parliament by Martin Schultz and a jury headed by the Italian writer Erri de Luca.

His following novel, Toutes les îles et l’océan (« All islands and the Ocean ») was published by Le Mercure de France in 2018.

His latest work is Pierre Mertens. Le siècle pour mémoire, a long literary biography of the Belgian writer Pierre Mertens (born in 1939), also published in 2018, by Les Impressions Nouvelles.

J.-P. Orban is a translator (Mark Twain, Hanif Kureishi), Director of a book series and an Associate-researcher in literature at the ITEM (Institute of modern texts and manuscripts) in Paris.

THE ENDS OF STORIES

1930. Vera is the daughter of Italian immigrants Ada and Augusto and is but a mere child in pre-war London. Brought up in Little Italy, Clerkenwell, she attends the Italian after school classes organised by Mussolini. And is dazzled by the mirage of fascism. But her dreams are shattered when war breaks out. Churchill turns on the Italian community and decides to « collar the lot ». In 1939, Augusto is imprisoned and shipped out to sea on the Arandora Star.

Vera then begins her search for identity, for place, for belonging. Ada, her mother, who speaks very little English, retreats into a world of silence and then into the attic. Vera throws herself into work, initially in a pseudo French restaurant in Soho. A child is born of her numerous wartime encounters, a boy Ben that she decides has a French father. So she learns French, and entrusts Ben to the French lycée in London. And from where he has to be removed, a total misfit. Lost between English, Italian and French, he retreats into mutism like his grandmother. And accompanies her on her wanderings through the city and its cemeteries…

VERA, which spans five decades of the narrator’s life, is a quest for truth, for identity. A tale of immigration, of the delusions of history, of the search for one’s roots. A reflection on language, on languages, on speech.

VERA’s narrative has strong resonances with current events and the question of integration of migrants. And the fascination of some of these youths in ideologies which bring them some roots, an (illusive) ideal and an identity they believe they cannot find where their elders have decided to settle.

VERA also provides a surprisingly vivid and realistic depiction of life in London, in Clerkenwell and Soho in particular, from the 30’s to the 60’s.

It is a moving and profound tale which has seduced numerous readers in French speaking countries, in Asia and in Italy.

The Ends of Stories, excerpts

1.

Did Churchill speak Italian? Did he know one single word of it? Would he have given his order if he’d formulated it in Augusto’s language? Do we dare, once we’ve made the effort to translate our thoughts into the words of another, condemn them to exile? Send them to their death?

2.

A lady, the ambassador’s wife perhaps, Mamma Italiana as we were told to call her, but perhaps the befana now landed and alighted from her broom – a tall woman, all dressed in black – moves towards the table. Her steps echo along the floor. She sways her hips and slowly walks on. You could say she exhibits in the room like a swan, a black swan on the edge of a lake, about to glide across the water. Her long, gloved forearm stretches out towards the table. Why is it that I only remember my name as if she’d called out just the one? Why is it that I only remember my name, as if it were the only one she called out? […] I suddenly existed, within the community where, at the end of the day, we all swarmed around like tadpoles.

3.

They were taken onto the wharves in the port. They numbered more than a thousand. Germans, Austrians, Italians and soldiers. The crew awaited them on the ship. A long gangway led up to it. But what struck Augusto was the immensity of the overhanging hull. He couldn’t recall having seen any others as high as this. Not in Trieste, twenty years earlier; boats weren’t as tall back then. Nor at the Isle of Dogs, as boats there were meant to navigate the river. The men on the quay were ants. A thousand ants waiting to board. Augusto looked upward towards the prow. At the end of the hull something was written. The ship’s name. But he couldn’t read it. I can, though, at the front of the liner. Arandora Star.

4.

Scylla and Charybdis. From misremembering the Mythology lessons at St Peter’s School – unless it was at Copenhagen Street – I believed for a long time that these names referred to innocent rocky islets at the entrance to the Straits of Messina in Sicily. Two columns forming Italy’s southern gate, in this Mare Nostrum glorified by il Duce. And I thought that if pillars like these existed in London they would be, on the one hand, Clerkenwell, the Little Italy where we lay rotting, and then Soho, the capital’s other Italian neighbourhood, at once sulphurous and more dazzling.

5.

‘When are you going to join us, Vera? History is done. It’s time for stories.’ […] It was during one of these exchanges that Seymour called me. And he was the one who came out of the nightclub and took me in. He spoke to me amidst the clatter of glasses and shouting revellers. I only understood half of what he was saying. The same went for him I’m sure. He’d been drinking, passed me his whisky, ordered another, chatted me up for a bit, gesticulated and sketched out the years to come: ‘No more blood, toil, tears and sweat,’ Churchill’s words at the start of the war, and I wondered whether, perhaps it was true, a page was turning – Winston’s, left in his war room with his fingers in a victory sign and a cigar in his mouth.